Ask or aks? How linguistic prejudice perpetuates inequality

Teacher and artist has been posting on social media about ālinguicismā after a reader asked him about the word āaxā, saying: āWhy did we struggle saying āaskā? Like when I was little, I always said āaxā. Like I couldnāt say the word correctly.ā

²Ń'°ä³ó±š²¹³Ü³ęās counters the common idea that āaxā (spelled also āaksā) is incorrect: āaxā isnāt a mispronunciation of āaskā but an alternative pronunciation. This is similar to how people might pronounce āeconomicsā variously as āeck-onomicsā or āeek-onomicsā, for example. Neither of these pronunciations is wrong. Theyāre just different.

Linguicism is an idea invented by human-rights activist and linguist to describe discrimination based on language or dialect. The prejudice around āaksā is an example of linguicism.

shows that the idea that any variation from is incorrect (or, worse, unprofessional or uneducated) is a smokescreen for prejudice. Linguicism can have serious consequences by worsening existing socio-economic and racial inequalities.

Flawed argument

Pegging āaxā as a mark of laziness or ignorance presumes that saying āaksā is easier than saying āaskā. If this were the case, we would ā and we never do ā hear ādeskā, āflaskā and āpeskyā pronounced ādeksā, āflaksā and āpeksyā.

The āsā and ākā being interchanged in āaksā and āaskā is an instance of what linguists call ā a process which is very common. For example, wasp used to be pronounced āā but the former has now become the go-to word. Many of the pronunciations bemoaned as āwrongā are in fact just examples of .

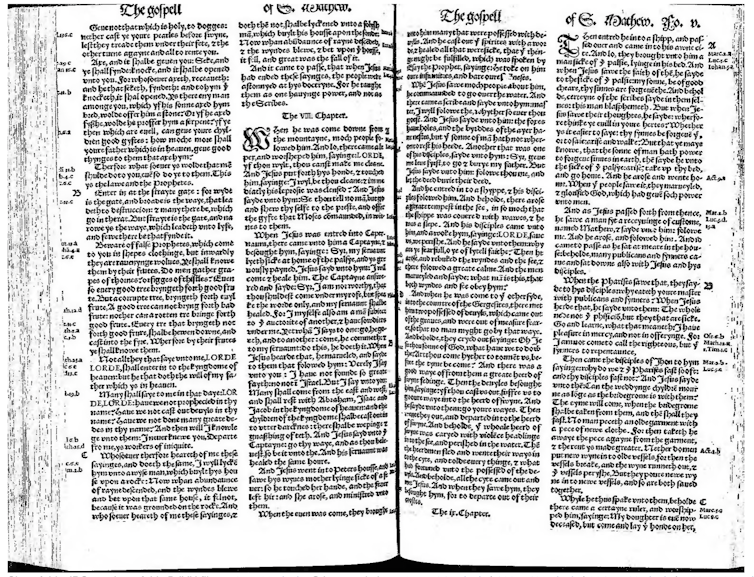

āAksā has origins in Old English and Germanic over a millennium ago, when it was a formal written form. In the first English Bible ā the Coverdale Bible, from 1535 ā Matthew 7:7 was written as āAxe and it shall be given youā, with royal approval.

Beyond written English, āaksā was also the typical pronunciation in Englandās south and in the Midlands. āAskā, meanwhile, was more prevalent in the north and it is the latter that became the standard pronunciation.

Contemporary prevalence

In North America, āaksā (or āaxā) was widely used in New England and the southern and middle states. In the late 19th century, however, it became stereotyped as exclusive to African American English, in which it remains prevalent. American linguist John McWhorter it an āintegral part of being a black Americanā.

Today, āaksā is also found in UK varieties of English, including . This dialect, spoken mainly by people from ethnic minority backgrounds, came about through contact between different dialects of English and immigrant languages, including , such as Jamaican Creole.

Multicultural London English was initially referred to in the media as āJafaicanā. That label wrongly reduced the dialect to something imitated or used inauthentically.

Other languages have, of course, influenced Multicultural London English. But the English language has been in a constant state of flux for millennia, precisely as a result of with other languages. When we talk about āsaladā, ābeefā or the āgovernmentā we are not imitating French, despite the French origin of these words. They have simply become English words. In the same way, Multicultural London English is a fully formed dialect in its own right and āaksā, as with any other pronunciation in this and other English dialects, is in no way wrong.

Linguistic prejudice

Accents or dialects have no logical or scientific claim to ācorrectnessā. Instead, any prestige of which they might boast derives from being spoken by high-status groups.

Many people now wag their finger at the word āainātā or at people dropping the āgā, rendering words like ārunningā as ārunnināā, and ājumpingā as ājumpināā. In, 2020, British home secretary Priti Patel of this mistaken criticism, when journalist Alastair Campbell tweeted, āI donāt want a Home Secretary who canāt pronounce a G at the end of a word.ā

Criticisms of ādropping gā exist despite the pronunciationās origins in Middle English, and not to mention the fact that well into the 20th century, the British upper classes spoke in this way too. This was satirised in a 2003 episode of the British comedy show Absolutely Fabulous, entitled .

Now that ādropping gā is stereotyped as working class, however, it is stigmatised as wrong. that linguistic prejudices, however unintentional, against immigrant, non-standard and regional dialects have held back generations of children from achieving their best in school and, of course, beyond it.

Schoolchildren who naturally say āaksā (or any other non-standard form of English) are tasked with the extra burden of distinguishing between how they speak and how they are to write. Conversely, no such barrier is faced by children who grow up speaking standard English at home, which can further entrench inequality. These children are already advantaged in other ways as they tend to come from high-status groups.

The way we speak has real implications in how we are perceived. in south-east England found that young adults from working-class or from ethnic minority backgrounds tend to be judged as than others ā a prejudice based solely on the way they spoke. The effect was worsened if the person was from ĢĒŠÄVlog or London, or even if they were thought to have an accent from these places.

The example of āaksā neatly demonstrates the absurdity, the baselessness and, crucially, the pernicious impact of deeming any one form of English to be ācorrectā. Accent prejudice and linguicism is a reframing of prejudice towards low-status groups who, simply, speak differently.![]()

, Postdoctoral Research Fellow (Institute for Analytics and Data Science) Department of Language and Linguistics, ; , Lecturer in linguistics, , and , Professor Emeritus of Linguistics,

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .