Strikes: why refusing public sector pay rises wonāt help reduce inflation

The UK government has the thorny issue of ongoing public sector pay disputes, despite the fact that these workers are from the cost of living crisis than their private sector counterparts. The pushing up , but recent data shows that giving these workers more pay is unlikely to have that effect.

In the year to October 2022, private sector pay increased by 6.8% only a 2.9% increase for the public sector. This disparity has lead to in recent months. On a longer-term basis, a growing pay gap is contributing to acute labour shortages, which is seriously affecting the delivery of public services such as and .

Voters largely support public sector workersā current industrial disputes. When a recent poll who they thought was responsible for the nursesā strike, nearly half (49%) of respondents blamed the government and only 20% blamed the trade unions. Another poll showed 55% of the public support teachersā current pay dispute ā up from ten years ago. Voters seem to see years of falling real wages for public sector workers as a problem, even if the government is not acting to raise them.

So why is the government refusing to offer a better pay deal to these workers? It argues that it is merely following the advice of the various which make recommendations on pay in the public sector. However, these bodies are not independent of government. For example, when the government imposed a pay freeze for workers earning more than Ā£21,000 a year in 2011 and 2012, these bodies followed this lead by making on pay for staff on higher salaries.

Fuelling inflation

Since industrial action first started to gather speed last year, about a causing entrenched inflation. This happens when rising prices prompt increased pay settlements, which in turn produce further price rises, wage increases, and so on. It happened in the UK when, similar to now, the rate of unemployment was very low.

Indeed, the unemployment rate is key to this discussion. In the 1950s, a New Zealand economist called A.W. Phillips showing an inverse relationship between wage inflation and unemployment in the UK that had existed for nearly a century, from 1861 to 1957. During this period when unemployment was low, wage inflation was high, and vice versa. Since then , as it has become known, has been widely used to measure price inflation.

If this relationship still holds, it would mean that the current low unemployment level of 3.7% could trigger a wage-price spiral, particularly if public sector pay is increased. So it could be argued that the governmentās refusal to raise public sector pay is .

But the problem with this idea is that the Phillips curve no longer works in Britain, as the chart below shows.

Unemployment versus inflation in the UK (2001-2022)

Using monthly data over the period from 2001 to 2022, this chart shows the relationship between inflation, as measured by changes in the , and the unemployment rate. Below an unemployment rate of about 4%, there appears to be a steep negative relationship between joblessness and inflation, in line with the original Phillips analysis.

But although this is happening right now ā inflation is very high ā it is the product of supply-side influences, not wage inflation. The UK (alongside many other countries) has been plagued by in recent years due to the effects of Brexit, the pandemic and the war in the Ukraine on the supply of goods and services. Recent increases in energy costs in particular have really boosted inflation over the past year.

At levels of between about 4% and 7% unemployment in the above chart, there is essentially no relationship between inflation and unemployment. The latter is expected to rise in 2023 , which means that raising wages in this situation will not affect inflation.

When unemployment exceeds 7%, inflation appears to increase alongside it, producing what is often described as āstagflationā. This occurs when prices and joblessness increase together ā a difficult combination for any economy to recover from, since it produces low growth.

This indicates that reasonable pay settlements in the public sector to compensate for falling real wages over the years could easily solve the present impasse without triggering a wage-price spiral.

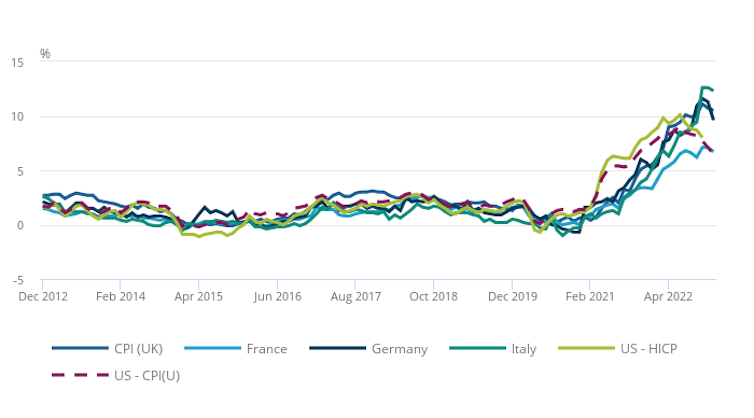

UK inflation outlook

This finding is reinforced by the widespread expectation that inflation has now peaked and will start to fall over the next few months. Indeed, the OECD is currently forecasting that across the world.

And for Britain in particular, itās also worth remembering that public sector employment is only a relatively small percentage of total employment, further reducing the prospects for a wage-price spiral caused by public sector pay rises. Private sector employment in the UK in 2022, implying that ācatch-upā wage settlements to compensate for declining real wages in the public sector would have much less impact on total labour costs than they would in the private sector.

All in all, the current government intransigence on public sector pay looks like itās based on both bad economics and bad politics. The former because there is little prospect of wage inflation at the same time as there is a serious labour shortage in the public sector. The latter because many voters think the government is basically hostile to the public sector.

This view could strengthen as the general election approaches. With the state of the NHS, in particular, set to loom large in votersā minds, this does not seem like a winning strategy.![]()

This article is republished from under a Creative Commons license. Read the .